|

|

|

| Jennings Family Memoirs | Page One | Page Two |

|

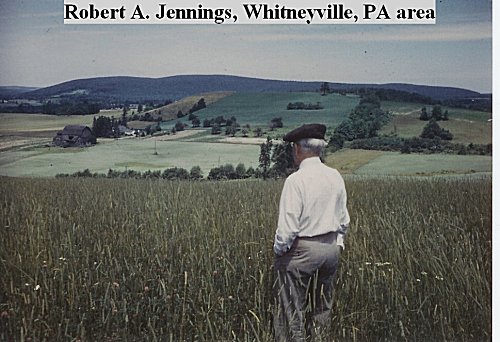

(By Robert A. Jennings Aug 22, 1882 – 19__) In one of the first frame houses in Tioga Co., PA, near the little settlement of Whitneyville, I was born on August 22, 1882. The building of this house happened many years ago, as my father and his sister were born here also, beyond that, back in the 1840’s some time, my grandfather, John Corbin Jennings, built the house for his new bride, Sara Sloat. It was quite an undertaking in those days, when trees were plentiful but mills for processing the lumber were scarce. |

Grandfather was a very ambitious man. He had some experience in lumbering, as he built and operated a gig saw mill for a number of years in the Pine Creek region near Tiadaghton, at Manchester, in what is now the Grand Canyon of Pennsylvania. I am not able to find out whether he carted the lumber for the house from this region or obtained it locally.

Mills in those days were operated by water power and there were none of those here, as this locality is situated on a plateau of 1800 feet above sea level, seemingly the top of everything. There was plenty of water for other purposes though, as there were many springs which helped in their way, to make, further on an accumulation of water for dams, mill races, etc. in later years.

Grandfather was born in Coventry, Otsego Co., NY near Bainbridge, Chenango Co., NY in 1811. At the age of 18, he walked from there to Tioga Co., PA, near what is now Whitneyville and acquired for homesteading a tract of land of about 100 acres. It has been said that he purchased it for fifty cents an acre, but I do not know about that. It was heavily timbered with pine, some of the stumps of which still remain. He then walked back to Bainbridge blazing a trail and encouraging some of his friends and relatives to accompany him to Pennsylvania.

Four families in all: that of Marcus Benedict, who had married grandfather’s sister Olive; the Pratts; the Virgilus Sweets; and grandfather’s mother Lucy; made the journey by oxen and sled. Here, by a small stream on what was styled "The Flat", he built a log cabin. I do not remember the cabin, but I do remember the chimney remains, some apple and plum trees, wild roses and an immense tansy bed. It must have been a lovely spot among the mammoth pines by a nice brook.

In imagination, I have a wonderful picture:

Forgetting the sad nervous part of prowling beasts and Indians, who were justly disturbed over the encroachment of foreigners on their land and in their midst, inside that cabin, small though it be, was love, friendship and happiness. There was the fireplace, shedding its heat and light from the crackling wood fire; the crane fastened into the stonework of the chimney, holding the kettle over the fire; its steam swirling around the room and up the chimney with the smoke; ears of corn on the cob braided together with the husks, hanging on pegs in the logs; and on other pegs, herbs hanging and drying for the necessary medicine. In a corner, is a framework of logs with rope strung from side rail to opposite side rail, on which is a mattress, made of husks, making a crude bed. By the side there is a cradle with a laughing mite inside. Mama or grandma is knitting socks while she rocks the cradle with her foot, and father is telling stories as he sharpens his axe preparatory to the next day’s work of clearing land. A floor of clay, packed hard and smoothed, was far from the fancy floors that we have to-day.

The Virgilus Sweets settled about a quarter mile east, on whose land "The Sweet Cemetery" was established. His sister and husband settled farther east, just south of this cemetery. The Robert Pratts settled a half mile south, on what is still called the Pratt farm, on the road between Whitneyville and Covington, PA. Mr. and Mrs. Pratt had a family of seven: Lura, Lewis, Sally, Edwin, Jerusha, Jane and Emily. Lura seemed most attractive, to my grandfather.

In a field in the north part of the little settlement of Whitneyville, by a nice spring, on the lands of Alozo Whitney, stood a log cabin, used for gatherings, church, etc. In this building in 1836, J.C. Jennings and Lura Pratt were married. In their log cabin on the "Flat", four children were born: Amelia, Almira, Joseph R. and Robert P.

On March 31, 1841, Lucy, his mother died and was buried in Mansfield, PA, before the Sweet Cemetery was established. On August 14, 1846, his wife died. There must have been an epidemic of some kind in 1844 because a number of children deaths are recorded on tombstones that are fast disintegrating in the Sweet Cemetery. Amelia, at the age of six, and Almira, at the age of two, died two days apart in 1844.

Robert and Joseph helped their father in the clearing of land and farming, perhaps also in building the frame house on the rim of the hill, a very sightly place until the call came for volunteers for the war that was brewing over the slavery question. Joseph enlisted and served three years. He was captured and became a prisoner in Andersonville Prison, where he died of starvation in 1865. Robert served a short period as a teamster, when he contracted typhoid fever and died January 30, in 1862. On the family tombstone in the Sweet Cemetery, the following names are recorded:

Born Died

John C. Jennings July 2 1811 Oct 10 1882

Lura, 1st wife of John C. Mar 9 1818 Dec 8 1846

Amelia Jennings Nov 18 1837 Jan 26 1844

Almira Jennings Mar 9 1842 Jan 28 1844

Robert P. Jennings May 21 1840 Jan 30 1862

Joseph R. Jennings July 20 1844 Dec 9 1865

The records of Susan C. and Charles M. are each found on separate stones and in different plots of Sweet Cemetery. Susan C. became the wife of Melville Green.

It has become a definite fact that there is, or was, an estate and money to the amount of four million dollars in England in the name of Wm. Jennings. Lawyers have volunteered to secure this amount for the heirs on a ten per cent basis, and for quite a time in the period of 1890 to about 1910, they worked quite thoroughly on the project, but the heirs had separated so widely that it became impossible to locate all and prove them, so the enthusiasm gradually died out.

It was said by the lawyers, that a quarrel ensued in the family and two brothers left England for America about 1760. The brothers were Darius Jennings and Joseph Jennings. Darius Jennings died in the battle of Perry’s Victory on Lake Erie, in 1812. His record up to the time of his death is lacking, at present, but there is quite a little concerning Joseph.

Born Died

Joseph Jennings 1882

Olive Jennings 1st wife

Beriah Jennings Dec 4, 1805

David Jennings Jan 26, 1808

Joseph Jennings, Jr. 1839

Sally

Stephen

???

??? Seventh child

Lucy Jennings 2nd wife 1771 1841

Lucy Jennings, Jr. Sept 23, 1808

John C. Jennings Jul 2, 1811 Oct 10, 1882

Eunice Jennings in infancy

Washington Jennings

Edward Jennings

James Jennings

Olive M. Jennings Feb 27, 1833 Nov 10, 1906

On July 29, 1793, Joseph Jennings purchased a tract of 100 acres, in Brandon Co., VT, for the sum of 20lbs.

On the 19th day of Feb., AD 1814, Joseph Jennings purchased of Abriam Babcock of the Town of Scipio, Cayuga Co., NY, a tract of land in the aforesaid Town and Co. of NY, containing 68 acres, sworn to and signed in the presence of Jas. Dorn, Judge of Court of Common pleas for said Co. of Cayuga and state of NY, Job and Abriam Babcock, Sally and Susanna Babcock, with seal, 2/19, 1814.

April 13, 1814, Joseph Jennings purchased of Timothy Church, Town of Jerico, Co. of Chenango, NY, 98 acres in same Co. and Town, with exception of one acre, three rods, containing sawmill of Jas Lee.

July 16, 1814, Joseph Jennings of Bainbridge, Co. of Chenango, NY, purchased of Eliza Jacobs of same place a parcel of land containing 24 acres, being a part of lot 47 of same Co., sworn to and sealed July 16, 1814 before Obediah Danks, one of the judges of Chenango Co., NY, Eliza Jacobs, Seal.

Feb. 16, 1816, Joseph Jennings sold for cemetery purposes, in the town of Coventry, one half acre of land for $19.00.

Nov. 25, 1828, Town of Coventry, Co. of Chenango, Joseph Jennings purchased a parcel of land containing 62 ½ acres from Samuel and John H. Walsh, trustees of the late Hugh Walsh, being a tract of land purchased by Hugh Walsh from Robert Harper in 1787, being part of lot, recorded in the secretary’s office of state of NY, as lot HW2. Signed in the presence of G. O. Fowler, with seal, Samuel Walsh, John Walsh.

Letters written by Lucy Jennings in 1828 said that she was very lonely, which sort of proves that Joseph, her husband, died that year.

In 1829, she accompanied her son, John C. Jennings on his trek to Tioga Co., PA. There is nothing to determine whether the log cabin was built before, or after this journey. She lived here until her death in 1841. If there were no cabin here when she came, it must have been quite an ordeal for a lady 70 years old, to start anew. There might have been other dwellings near, but, to my knowledge, there is nothing to show, unless in the little settlement of Whitneyville. Anyway, 16 years were spent in this log cabin among the pines. Whether they could have been called happy years, or not, that seems to have been as good as was then known. If there were hardships, well, they surely lived above them.

In 1846, Lura, the wife, passed away leaving two boys without a mother’s care, so, in 1847, a new mother came into their life. Miss Sarah Sloat became the new wife of John C. Jennings. In the meantime, the house on the rim of the hill overlooking the "Flat" was being constructed. The location could not have been better chosen, for as the timber was cleared away, a grand view was disclosed in two directions. To the east, could be seen the homes of the Sweets and the Benedicts, to the south, the Pratts and the home of wife Sarah, who later became to my brother Ralph and me, the greatest grandmother in the world, so kind, gentle and sweet. Thus she seemed to all who knew her.

To this marriage of John C. and Sarah A., five children were born: Alfred, Orson, Henry, Susan, and Charles.

Alfred, Orson, and Henry died in infancy. Susan grew to womanhood, became a school teacher, and later, became the wife of Melville Green, a native of Whitneyville, son of Nelson (1819-1892) and Emily (1828-1933) Green. Susan died when her only son, Rupert, was two weeks old. They had also an adopted son, Basil Ferry Green, who was the son of Charles and Ida Ferry. Ida Ferry was a sister of my mother.

Charles M. Jennings grew up trying to help his father on the farm, but his heart did not seem to be in farming. He has told me many times of his leaving without notice and remaining with relatives or friends, miles away, for two or three weeks at a time. I have asked him if this did not worry his parents, and he said "I guess not, for they knew that I’d come back when I got ready". He has told me that he had a girl friend that lived by the elm tree that stood for years in the middle of the road near Daggets Mills on the road between Elmira and Job’s Corners, and of his walking over there to see her, maybe going to a dance and then walking home in time to help with the chores in the morning, perhaps going cross county a distance of 15 miles each way.

Many times in later years, as we would be driving to work at the carpenter trade, we would pass through a certain section of the country that would bring to mind certain happenings of his, as in a swampy section, he’d say "I remember of working one Summer cutting the swamp grass with a scythe and dragging the hay out to dry land after piling it on a sapling with part of the branches removed.

In those days, there used to be hop vineyards. Poles were fastened in the ground on which the vines would grow to a height of 10 or 12 feet. Girls were hired to pick the hops. He told me of his placing the ladders, removing the baskets, etc. and what fun he used to have with the girls. He used to make dates for dances and had been known to place a ladder to the girl’s bedroom window, so that she could sneak out after the parents thought she was in bed. But he always made a point of getting the girl back home before getting up time.

One time, he operated a shingle mill for Spencer Crittenden in Crittenden Center, where Hills Creek Lake is now. One day Mr. Crittenden had gone away and cautioned my father not to run the mill. But he thought that was foolishness, so he started the mill and was busy at work when the check on the steam line broke and all of a sudden, the mill broke a record for speed and nearly wrecked everything before he could draw the fire to lessen the steam pressure.

Father’s talent seemed to be along the line of wood working. He persuaded Alonzo Whitney to teach him wood turning, a trade at which he became very proficient. In his eagerness, he made his own lathe, operated by foot power. A sample of work can be seen in the porch of the house of Jay Whitney, in Whitneyville, and elsewhere in that locality. He built a shop on the old farm and here, I helped him pump the old lathe until it seemed my leg wouldn’t operate ever again.

I am sorry that I do not know much more of my father’s growing up, but to me, he became about the best father in the world. In 1880, when he took off on one of his journeys, he happened to meet up with a girl by the name of Emma A. McLean of Hammond, who was on an excursion to Watkins Glen, NY. There is where he met his Waterloo, and on Oct. 20, 1881 they were married in Mansfield, PA, in Bailey Hotel, then came to the old farm to live and help his father with the farm work. Here on Aug. 22, 1882, a son was born, Robert A. Two months later, not being able to stand the strain of seeing me, my grandfather died, October 10, 1882. Grand mother liked me, so she helped carry on. Then on May 21, 1884, a real guy was born and they named him Ralph. Grandmother was still glad.

My grandfather, John C. Jennings must have been quite a wonderful man as many instances have been related of his kindness and generosity. My father told of his selling a load of hay to Julius Bailey. There were no wagon scales in those days, at least not handy, so a person’s "guesser" had to do the job. They used to load the hay from the mow where it had cured, to a rigging on the wagon, for a well proportioned, good load, then backing it out of the barn, would rake off all loose hanging strands, stand back, observe and estimate. Finally it was judged to be a ton, scripture measure of course. When satisfaction was reached, Mr. Bailey said "Well, Uncle John, how much do I owe you?" To this grandfather replied "Ten dollars". Mr. Bailey said, "Mercy me, Uncle John, has is selling for twenty dollars". "Makes no difference" was the reply, "Hay is worth only ten dollars of any man’s money, so take it and get out of here". Of course he was selling to his niece’s newly married husband, which might have made a difference, but from all I learn, this was the kind of man that he was. How much better this world would be with more Uncle Johns. I am very glad to be a descendant. Maybe if he had lived to know me better he would have bee satisfied to stay a little longer, but when we are called by Him that ruleth over all, there doesn’t seem to be much that we can do about it.

Taxes in those days seem to be more humane, for here is notice dated July 12, 1870.

"Jennens, J. C. Taxes.

County 6.24

State 0.23

Poor 1.04

Cev Poor 3.64

School 7.24

18.39

Notice 30 days J.M. Wilkinson Col."

There are many letters written back and forth to his sons and other’s sons that were trying to do what they thought was right in the war that was going on in the South in 1861-1865. I have many of these letters in my possession, most of them headed by "Most respected parents."

Can you imagine the feelings of sons, far away from home and, in those days, poorly clothed and poorly fed, asking for some clothes or a box of food, and the feelings that parents had? To me it seems pitiful and sad, but it had to be that way so it seems, for the sake of freedom and what was thought to be right. Many letters tell of receiving socks, soap, cake, etc., and how they were appreciated. Then the time come when the buddies would write for their sick or injured friends who could not write or that so and so had been captured. These buddies were very kind in trying to keep the parents well informed and to keep them from worrying. The following few letters are samples:

Camp, near White Oke Creek Va. Nov 10 1862

Respected Parents, I now seat myself to answer your very welcome letter at hand this morn and I was glad to hear that you was well, Pa

You said you had got your fall’s work done: I wish I was there to drive those little red steers they must be large cattle by this time.

About my not saying anything in my last letter about Philemon. He was left behind when we left Pleasant Valley but has just come to the Regt. today His leg is not much better and has been examined 2 or 3 times and pronounced unfit for duty and his discharge has been made out 2 or 3 times and sent to be sined and I suppose they are lost, something ought to be done for it may ruin his leg::- He cant do duty so he might better be home than to be here, He is erning 13 dollars a month, - better than he could at home,

Well Pa we left Orse back to a place called Waterford, he was unwell so he was not able to march not very sick only worn out and that march through Maryland was hard on him, Fresh meat without salt and he got dysentery,:-now don’t worry your self about him for he will soon be with us again, don’t tell his folks if you can help it.

So I must close so good bye

From your son JR Jennings

To John C Jennings

Camp in Rear of Vicksburg July 27 1863

Dear Parents, again I seat myself for the purpose of conversing with you at home by the silent language of the pen,:--U segd my compliments to you mother for writing such a long letter, I wish you would do so every time (etc::) I will tell you about our march we left camp last month on the 29th and started for Jackson the capital of Miss

We marched about 6 miles and camped, staid there till the 4th of July then took up our line of march at 4 oclock, P.M. we marched until about 9 then stopped for the night, the next morning started again, we commenced skirmisning before Jackson, our Regt was all deployed as skirmisher

We had a skirmish line about 7 miles long, we did not meet much but cavalry the first day but the 2nd day morning we had not advanced far when they poured a volley into us, we returned the compliment until we got out of ammunition, Mafs Vol relieved us and before we left the field they fell back about 10 rods and there they held them.

Neither party advanced, we was retired by 2nd Div of our corps There was not much fighting on the 27 The "Rebbels" all left and our men took possession of the City must close so good Bye

J.R.J.

Camp 45th Regt, Pa Vol,

Near Annapolis Md Mach 21st 1864

Mr. John Jennings,

Dear Sir

Today I saw a man from Richmond and even from Belle Island where your son Joseph was when this man left about a week ago, since, he said they have left for Georgia

He also said that Joe was enjoying good health

They are likely to fare much better in Georgia than at Richmond

Yours truly

R G Richards

To John C Jennings

East Charleston Tioga Co. Pa.

Jarvis Hospital MD

Feb 16th /65

Dear Friend,

This morning I received your letter with $5 and glad was I to hear from you, I would have not scent fro that money but it seemed to me as though you was the only friend that I could receive the money from in due time, I am ever thankful etc,etc.

This from your true friend

Jon W Fenn.

Other letters acknowledge many deeds of kindness such as loans, gifts, caring for property of boys in service, etc etc.

In January 1862, work came that Robert P. Jennings was very low with fever and was not expected to survive and later came the notice as follows:

Washington D.C.

W.M Hospital, Jan 30 1862

I certify that Robert P Jennings died this morning of typhoid fever

(Signed) J. T. Young

Medical Asst.

In 1863 word came from a buddy of Joseph that no letters were allowed from his Regt. Because of the necessity of secrecy, then a little later, it was announced that Joseph had been captured a Clinch Gap Dec. 14 "63 and probably taken to Andersonville. He was taken to Libby Prison and transferred to Andersonville and here he was held prisoner for over a year in this horrible place where, as an article in the National Tribune by one of the soldiers, describes in this way: "Not a tithe of suffering and misery can be told by the boys who had to live here." And here he died of starvation in 1865.

I guess the feelings of these "most respected parents" could never be expressed in words, but they had the good courage to carry on. The bodies of those half uncles of mine, are resting in Sweet Cemetery, where Old Glory waves until the flay flutters it’s last flutter and a new one is placed there by G. A. R. in respect to their noble sacrifice. The same can be said of hundreds of other sons and parents.

Now we are enjoying life where freedom reigns, purchased at such a horrible price by these heroic souls. Can we ever forget to do them honor?

Among the letters from the boys, I found a duplicate of treasury certificate as follows:

Nov. 13, 1865. Duplicate Treasury Certificate #202238 for $426.66 Payable to father of Deceased, being for pay due Jos. R. Jennings, a Corporal in Captain Richards’ Co. G. 45th Regt., Pa. Volunteers for services from June 30, 1864, when last paid, to Dec. 9th. 1864 time of his death.

Rations from Dec. 14th ’63 to Dec. 10 ‘64

Signed E.B. French 2nd. Auditor.

As stated before, Joseph R. starved to death in Andersonville, but with rations coming 6 years too late from the North, even with the help of his buddies, how much better it could have been. Of course the North took care of its own, we know, yet the North had their serious difficulties.

In journeying up and down Pine Creek, Penna., the wonder has been, just where was grandfather’s mill located, and up to this time no knowledge has come as to it’s location, but as nearly as anyone knows, it was 9 miles below Ansonia, according to my father’s recollection, and would be somewhere near Tiadagnton or Blackwells. These places at that time were the only places reached by wagon. Floods in the valley completely obliterated the town of Manchester. Pine Creek, itself, was declared a public highway by the legislature, March 16, 1798. Pine Creek Valley and stream also, was a route of travel by the Indians from Jersey Shore to Genesee, home of Mary Jemmison, the white woman ruler of the Indians.

My father told that the mill operated by his father was a "strap" mill, or in other words, a jigsaw mill, where the saw, a flat blade, traveled up and down and was operated by water power. This was a slow process. While the lumber was being sawed, there was plenty of time to do the other necessary work, such as getting another log ready, arranging boards for edging, and piling.

History of Tioga Co., published in 1896, says that this mill was located at Manchester, where in 1829, Leonard Pfoutz erected a sawmill and gristmill south of Ansonia. Leonard Pfoutz sold his mills to Stowell & Dickinson in 1833. Mr. Dickinson was a native of Bainbridge, NY, the childhood home of John C. Jennings and perhaps this is one reason that John C. Jennings established or operated a mill in the Pine Creek region. It is near what is now (1958) Leonard Harrison State Park, on the Grand Canyon of Pennsylvania. This region is said to have contained the prize pine the like of which cannot be purchased now.

The gristmill was no less a necessity than the sawmill but before grain could be ground, it must be raised, and grain could not be raised until the land was cleared. Hence the sawmills were established.

For several years, the settlers were compelled to go to Jersey Shore or Williamsport on the south or to Tioga Point, Elmira, or Painted Post on the north, to have their scanty supply of grain ground. Many stories are told of the dangers and hardships during journeys to and from these mills.

After 12 years of lumbering in this region, my grandfather returned to his farm, to remain a farmer until his death.

A friend of mine by the name of Chester Sykes, who grew up in the lumber woods, working for a long time for the Goodyear Lumber Co., of Galeton, has told me many stories of exploits in the woods. He drew for me a longhand map of the railroads that were built throughout this region to haul the logs to the mill. This was very interesting indeed. The pattern is similar to the arteries in the human body, branching from the main line to all parts of the forest. The mills have now all disappeared and scarcely a trace is left. Many serious floods have done their part to destroy evidence. A log road used to skirt the rim of the Grand Canyon through Harrison Lookout.

The history of these lumbering interests is indeed interesting. Getting the product to market was sometimes very perilous, as it had to be flooded down the creek at high stage to Williamsport or near. And the getting the logs to the stream by those who chose to raft them to Williamsport, was a rough and hazardous job. Slides down the steep mountainsides were made by making a trough of slabs, or the rounded edge cut from logs, with the outer side up. Horses drew the logs to the head of these slides, which sometimes were nearly a mile long, and then they slid down to the creek at a tremendous speed, boomed and splashed. Each log was branded on the end with initials of owner much like steers are branded to-day. All in all, lumbering was big industry but the first operators eked out a mere existence. There used to be a mill on the Petrie farm at the foot of the hill by the old homestead which I can remember very well. Alonzo Whitney established in Whitneyville, a carding mill and sawmill in about 1865, and there most of the timber of this locality was sawed. Mr. Whitney was an expert wood turner, and in a shop across from the mill, he taught my father the trade. After Alonzo died, his son, Nelson Whitney, carried on these ventures. Of course changing times caused them to gradually disappear.

In this sawmill when I was 14 years of age, I worked for 35 cents a day of ten hours, wheeling sawdust. The saw was located on the second floor and it was my job to keep the sawdust away from the chute that emptied into the room below, wheeling it in a wheelbarrow to the pile about 30 feet from the mill. Getting rid of the hardwood sawdust, keeping the chute clear, was not too bad, but when basswood logs were sawed, I just could not keep up, because the wood was soft, the log on the table traveled faster, making more sawdust. Sometimes the sawing would stop until I caught up. At one of these times Mr. Whitney was talking to a man in the log yard seated on a log when he called to me. I replied that I did not have time, which was not the proper thing to say to the boss. He insisted so I ran over and hastily asked what he wanted. He said "Sit down." I said that I couldn’t for the mill would stop and about that time, it did, and they began looking for me. I said that I have to go. He said "you are working too hard, sit still." I did but I didn’t feel like doing it for I knew that I would only have to work harder when I did get back. But he was the boss and if the mill shut down, it was his business and from then on, I received my first 50 cents a day. An increase of 15 cents a day was quite something in my young life. Later, I piled lumber and did various things and was very glad to be working around machinery, as boys are usually glad to do. Yes, those were the "good old days." I received 20 cents for packing a thousand shingles in four bunches. Of course things were done in a crude way, as we would think to-day, but it was thought OK in those times.

The sawmill was a great curiosity and people would come in and watch. I remember one time a young man stood on the stairs with his head and shoulders above the floor, watching the log carriage go back and forth, when all of a sudden, the lubricator valve on the steam line blew out letting 250 lbs. of steam loose only a few feet away from the man. Suddenly he thought it was no place for him, and started to run, never stopping for lumber piles or logs. He jumped over them and did not stop until he had reached the limit of the mill lot, thinking all the time that this is the end of things.

The logs were drawn into the mill up an incline on a can that would carry three logs. By a cable that wound around a drum and was operated by a loose belt that tightened as a lever was pulled. It seemed great sport to ride down and then back on the logs.

Life was young then to and very happy. Directly across the road in front of the mill, was a blacksmith shop, operated at this time by Mr. George Abrams, and back of this shop, was a room used as a carpenter shop for making bob sleds, wagons, etc. which were ironed by the blacksmith. Here my father would repair the broken sleds, in log hauling time. It seemed a great thrill to be able to go with him and watch, and it would be a great curiosity to watch the sparks fly as the smithy pounded the hot iron and to see him shoe the horses. I can still remember and can almost smell the shavings that he pared off the horse’s hoofs.

My mother’s father (McLean) was a blacksmith at Hammond, PA and she told him one day that she would like to learn to shoe horses. He, in fun, said that a person could not become a blacksmith until he had eaten a pound of hoof shavings. Next day he asked her what was the matter, as she was chewing something and making an awful face. She said "I am learning to be a blacksmith" to which he replied "By Gob (his favorite expression) don’t you know any better than that?" She said "you told me to do it". Well, she never became a blacksmith to shoe horses, but she did become a very good pie maker, and learned to shoe flies, which were a great nuisance in those days. It was pretty hard job to be able to eat a decent meal without getting a fly or two mixed with the victuals. They made a unique contrivance for scaring the varmints by cutting a flour bag into strips about ½" wide, left together for about three inches, that could be wrapped around a stick, such as a cut off broom handle. It was the task of one of the children to flourish this tool around the table while the rest ate. Next meal, it was another one’s turn. But still they had some very foxy flies in those days and some would meet destruction in the gravy or the butter. Of course the butter and gravy could not be always watched or wasted, so the fly was dipped out and transferred to the cuspidor or coal scuttle whichever was handiest. Yes, those were the good old days. It was not the best of thoughts to wonder where that fly had been in its travels. The meal tasted good so the fly was forgotten. It was such a common occurrence that it did not pay to be too finicky. Most of us grew to manhood and enjoyed a healthy life. Memories can be very precious, if they happen to be the sweet kind and a horrible thing as well, if their making happens to be in the wrong direction. Every person, I presume, has had some memories that he is trying to forget.

I do not profess to be different from the average or to have climbed very high on the ladder of success; nevertheless I have some priceless memories and am very happy with them. I am enjoying life, and the beauties of nature, a firm believer in a Supreme Being who rules and guides us all if we put our trust in Him.

This experience has been most happily proven, many, many times. You, my dear reader, may have experienced the same, if not, why do you not give it a try.

The old home, as Winter was beginning, was banked with sawdust or some other substance such as straw from the horse stables, to keep the cold from penetrating the cellar wall, her we had some very cold weather with the temperature reaching a low of 35 degrees below zero and the countryside covered with a blanket of snow to the depth of the zig zag rail fences and sometimes completely covering them, and then again, at times a sleeting rain would make a glare of ice covering the snow. I remember the boys and girls of the neighborhood would skate all over the countryside. It was s wonderful time to ride down hill, except where did not seem to be much control of the sled. We tried all sorts of contrivances for riding downhill on this crust. We made some holes in barrel staves through which we threaded rope to tie them to our feet, but this did not work out too well as the ropes soon wore out and then we would almost come apart in the tumbles we would get on this icy snow. Kids, 8 or 9 years old do not know much about mechanics, but you can’t say that we did not try something, which is a good sign of progress. Then we got the large grain shovel, called a scoop shovel, molded of metal, with the idea that we could sit in the shovel with the handle in front to steer. Not a bad idea but it did not work, the steering apparatus just wouldn’t work and the shovel would turn around, go side-ways or almost any way, going pesky fast, too fast, really for we could not get off, once we had started. The friction caused the shovel to get very hot, so we had to give up the idea as we were afraid of having smoked hams. Even as it was, we carried blisters for some time and had to sit down standing. We tried anyway.

Another way of having fun riding down hill was for older people. They would get what was called a cutter, a fancy sleigh for two people that had two runners on which was fastened the body or seat by spokes, called knees, about 15 inches high and well braced by fancy iron work. To this was attached thills inside of which the horse was hitched, these being so arranged, offset so that the horse could travel in the track made by the runner, as there was always a ridge in the center of the road, called a comb, sometimes 12" high. These thills would be removed, then someone would get under the cutter on a handsled and by gripping the rear knees, could guide the cutter amazingly well. They had many nice times, but it was no job for us smaller rascals, we were scared to try.

When hunters were trying to shoot grouse, they would often scare them out of the woods into the open country. They would dive into the soft snow and travel really quite a distance underneath, but when they tried it with the crust on the snow they would get a broken neck. This icy snow was not so good for the animals either. Some would starve. Lots of young trees would be killed by rabbits chewing the bark for food, and when spring came, it was queer to see these trees girdled so high from the ground.

The snow would drift around the house until sometimes it reached the middle of the windows, and with the hard crust, it made a nice roof to the tunnels we would build under the snow. We made rooms with doorways like a house. Being cold, the snow did not melt on our clothes, and out of the wind that pierced to the core outside, we had some wonderful times.

During the process of one of these storms, my father was working at his carpenter trade about 2 miles away in the country. In the morning when he went to work, it was the beginning of what looked like a very nice day. He traveled to work by a horse and roadcart. A roadcart in those days was a two wheeled vehicle which sometimes was equipped with a set of coil springs suspending the seat, making it easy riding. Without these springs, it was not so agreeable, as the jogging of the horse gave it a peculiar teetering motion.

Well, my father, being always so interested in his work, did not notice the beautiful snowflakes that were fast falling in the middle of the afternoon, nor the moaning of the wind what was increasing in intensity, nor how dark it was getting before it was time to get dark. When he started home, there was plenty of snow where the wind had not blown it away and for a mile, all things were well until, all of a sudden, the horse stopped. When told to go on, he just didn’t do it. So father jumped over the wheel and landed in four feet of snow. The kind horse had struggled as hard as it could, pushing the snow ahead until it just could go no farther. Father spent two hours tramping the snow, making a path for the horse and when he arrived at home, both he and the horse were exhausted. Mother became so worried when he did not come that she was crying quite hard and scared us boys very much. She bundled us up and we made our way to the barn to see if the cows were all right. They had been put in the barn early in the afternoon because of the storm. And then we went to the sheep shed to see about the sheep. The sight that we saw was something to remember for the sheep were completely covered, making the nicest, rounded mounds. They were all right but 50 or 60 pounds like that were a sight to behold. They were not harmed, as breathing is easily accomplished in light snow, and they seemed contented. We then went to the horse barn which was near the main road that passed near the front of the house. Here, we found a horse loose and eating out of the oat bin, which is bad, for a horse can easily overeat and get too many vitamins. We did not know about vitamins in those days. While mother was trying to get the horse back into its stall and tied, father arrived. Then mother really cried, but for joy. Father and the horse were so covered with snow that they looked like ghosts. I can now realize how she felt, but I could not then. Isn’t it strange how it takes jars and jolts like this to bring us to our senses enough to realize how much we all mean to each other and how much we depend on the other one?

From then on through the winter until sometime the beginning of April, the real roads were obliterated and the traveling was done through circuitous routes through the fields, fences being opened if necessary. In January, near the middle usually, came warm spell which we called the January thaw. The snow began to melt, settle and become soft. The roads and become packed hard to sometimes 15 or 20 inches above the ground, by the sleighs as there were no autos then and the traveling became very treacherous. The horse’s feet would break through and when night came with its freezing temperature, these holes would freeze. Did you know that a hole could really freeze? If the horse happened to step into one of these holes, it could easily have a broken leg and if it happened, the horse would be shot. They did not seem to mend broken legs in those days, at least on the animals.

We used to think that the winter was half over at the time of the January thaw and that is what it seemed. Winter, even if it were very cold, was a very happy time, with all the sleigh ride parties, snowshoeing, riding down hill, skating and so forth.

At Covington, PA was a glass factory and many sleighing parties were entertained by the glass blowers, by their making various ornaments with the glass. The girls seemed to be the always most favored. Sometimes there would be snowball fights with the youngsters of the town, started in fun, or course, but at times, became quite serious. It was really great sport when 20 or more boys and girls would go on one of these sleigh rides. You people that grey up in the automobile age, are enjoying the advance in transportation, but you cannot know the thrill and enjoyment of the old fashioned sleigh ride, and all the fun to be had in the country, where your elbows were not punching someone in the ribs.

We used to put the wagon box on the bobsleds and in this box place six inches of straw, put blankets, maybe, on this straw and sit down on this, partly out of the wind, and could ride very comfortably in quite cold weather, telling stories, singing etc.

One time, I was asked to drive one of the sleighing parties to a young people’s meeting quite some distance from home. The man that was supposed to do it couldn’t for some reason. He furnished the team and had borrowed some fancy bobsleds. In those times, we had a variety of sleighs, the same as a variety of autos is at hand now. Well, we went to the meeting and took an active part, and then, on the way home, someone suggested that we should stop in Wellsboro at the glass factory, which we did and were entertained royally by the workers. As we went to the sleigh to go home, we found that one horse had become sick or something and had fallen down, breaking the tongue of the bobsleds so that the sleds could not be used. There we were, 7 miles from home with two feet of snow on the ground. One of the girls in the party had been working in the home of the owner of the Dart Carriage Factory in Wellsboro, so she and I made a trip to his house, and at 2: am he laughed and said that there is not a thing that I can do for you except to loan you a wagon. Imagine our feeling driving wagon home in two feet of snow. The wagon tracks are about one foot wider than sleigh tracks, thus putting one wheel of the wagon into snow that was softer than that of the beaten packed track of the other wheel. So we tipped on way and another as the wheels slipped off the track but, after two and a half hours, we arrived home, where our parents were wondering if we were lost or damaged. We had lots to tell the next day when we were questioned by our school mates. Then I had to make another trip, with the necessary supplies, for the abandoned sleds, and had to get father to make repairs before delivering them to the owner.

When I think of the many times that my father has helped us, as well as other people, out of difficulties, I seem to think that he was another wonderful man like my grandfather "Uncle John". He also had a shop in which he made bobsleds, heavy ones for logging, fancy ones for lighter work or pleasure and did repairing, etc., which kept him quite busy during winter.

There was a stage route from Mansfield to Wellsboro, which carried passengers and also delivered mail to the post offices on the route: Marden, East Charleston and Charleston. As the passenger traffic was quite heavy, the driver had a large covered wagon, called an omnibus. The heavy vehicle and the 14 mile trip each way, was very trying and tiring for the horses. When the snow was deep, he sued sleds but as warmer weather came, part of the roads were bare where the wind had blown most of the snow away, he had to resort to the omnibus, which meant that the bad spots in the roads had to be shoveled out. The whole populace would assemble and shovel. The hill by the old homestead, called the "Jennings hill" was usually drifted full to the height of eight feet. I can remember the doctor in his two horse buggy, making his rounds, being out of sight in the newly shoveled snow, with just the ears of his horse showing. This newly shoveled road made wonderful place to slide down hill, and all the youngsters of the locality would assemble. The sliding finally made the road very smooth and slippery. When the stage came along, the trouble that was encountered in getting the heavy bus up the hill, caused the driver to curse us poor innocent beings, and to make the riders disembark and push, with us kids too scared of the driver, to get near enough to help.

Skating in the locality was not of much account for the only places available were small fish ponds privately owned, the nearest one of which was owned by John Kohler, who lived directly opposite of the log cabin on the flat. We had lots of fun here though for it did not take much to give us little shavers a thrill.

I remember when the pond was made because of the way they did it. It was scooped out of the ground a short distance from a nice spring of water, by ploughing a while, then dragging out the loose dirt, then dragging out more after ploughing until the right depth was reached. Then it was sprinkled well, sheep were put into the hole and driven around and around. Then, I thought it a great curiosity, little realizing the reason, until later we found out that this was done for the purpose of puddling the clay bottom, so that it would seal the pond against leakage. It seemed to work perfectly for the pond filled and remained full.

It is said that a man traveled through the country persuading the farmers to build ponds and stock them with fish what he would supply. The fish were carp, a very poor grade of fish for eating, as they found out, and the fish craze soon diminished. These ponds later became very valuable, as they were a source of water supply in time of drought, and farmers would come from far and near for water to water their stock. I have helped do this many and many times, and I guess that this storage of water was an act of God.

We used to harvest ice in the winter from these ponds of clear water frozen to a depth of 12 to 20 inches, by chopping a hole for the starting place of a crosscut saw, that was ordinarily used for sawing wood, a saw about five feet long with a handle on each end. Removing one handle, they would saw the ice into blocks about 16 inches square, load them on bobsleds, haul them to a building that could be used for the purpose, and pack them tightly in the center of the building. They covered the pile with sawdust to a depth of about two feet. Ice, in this condition, would last well into the summer. It was usually a community affair, where they could get ice for making ice cream, cooling milk, etc.

The older people used to assemble at some neighbor’s house for an evening, tell jokes, sing, and then have ice cream and cake. One time we were having one of these funfests, assembled at the home of Captain Whitney. His daughter, Jessie prepared the cream for freezing. Usually the young boys of the parents would get the ice, chop it up in a tub, or occasionally place it into a bag and pound it to break it into small pieces, then with the salt added, pack it into the freezer and take turns turning the crank, which we were willing to do for the reward of cleaning the paddle when the job was done. It was not a very nice name for the job of cleaning, but we called it "licking of the paddle." This particular time could be remembered, for when we made a scramble for the paddle, our hopes were quickly subdued, because Jessie had reached into the cupboard for the vanilla and had obtained the arnica bottle. Arnica was used for aching muscles, and such, and was not supposed to be used to season ice cream. I remember that it tasted horrible, similar to skunk smell. Well, the ice cream part of the party was a failure, but nevertheless, it provoked much laughter and was passed off as a great joke.

Finally winter passes, spring begins, and still with plenty of snow, there is a wonderful feel to the air and a wonderful pep to the constitution. Maple sugar time approaches, the sun shines warm on the side of the straw stack at the back corner of the barn, the lambs in the sheep pen are having a very happy time racing and frolicking, and I used to sit by the hour in the warm, sunny side of the stack, protected from the wind, watching the lambs which I loved so much. The interest in them was to be a great help to me in later years.

My father used to pasture sheep for other people, taking his pay by having half of all the lambs, and in this way, he acquired quite a flock of sheep of his own. As a usual thing, sheep do not need much care. They can find their own food if the snow is not too deep. It seemed to be my job to see that they were in the right pasture, or if allowed to run free, to watch and see that they did not stray to some other farm. I loved to do this and the sheep seemed to like to have me do it. I remember that we had a papa sheep, that ordinarily, was very docile, but sometimes when molested or bothered, he would get a little ugly. Their mode of defense was the act of butting with the head, usually quite effective, and for that reason, he was very much respected by everyone.

There was an elderly man staying at our house one time. He had very poor eyesight. Over one eye he had a leather pad, in the center of which there was a small hole that enabled him to see fairly well after the extreme light was diminished. One day, he was groping along the barnyard fence, feeling his way to the bars of the gate. He let down one bar, or rail, as it really was, and was stooped over in position to crawl through, when papa sheep decided that that was the right position for helping, which he did in a commendable manner. After that, the poor man thought it best to inquire where the sheep were. Surprises like that are most too sudden to be enjoyed or joked.

On day on another occasion when my brother and I were getting the sheep into the pen for the night, this ferocious animal was inclined to have a little fun with my brother, and my brother noticing it, said as he clenched his fist and got them into pugilistic fashion, "Oh you would like to butt me, would you?" The sheep did not wait to answer, except with the real thing, and when brother picked himself up; he was on the other side of the fence, having gone through without opening the gate. That was the last time that he tried that stunt.

Brother Ralph was pretty young to be of much help yet, but he was everywhere that I was, like a shadow and soon was to be a great pal. That is one reason, and I guess the main reason, why I was to enjoy boyhood so much back there on the dear old farm.

Spring was in the air one fine sunny day, and as father was home that day working at his trade in the shop, repairing a set of bobsleds for a neighbor, we asked him if he wouldn’t help us tap some maple trees, that were near the house. We very innocently did not know that there had to be equipment for such an undertaking and he asked how it was to be done. Our inventive minds were not yet in the process of operating or at the right stage anyway. But where there is a will, there is a way. So after thinking a while, daddy said, "All right, we will find a way." And from that day until this, that phrase has stayed with me, we’ll find a way. That was the best lesson I have ever learned. I am sure that he did not know then, just how much good he was accomplishing. Anyway, he took a saw in one hand and my hand in the other while I took my brother’s hand; with high spirits and high faith in my father, we knew something was going to happen. And it surely did. The foundation to almost everything was laid right there. I would give everything, as the expression goes, to be able to tell my father what he did for me that day. Looking back now, I think that before the day was over, that he was as happy, and maybe more so, than we were. He seemed to enjoy it very much, I can still remember the thrill, when we went to a hedgerow, and finding some alder bushes, he picked out some branches of suitable size, then, going back to the shop, he cut them into six inch lengths, sawing them lengthwise in the middle to within three inches of one end, he punched out the pith with a stiff wire, leaving about 1/8" hole in the three inch end and a channel in the rest of it.

This brings to mind the poem of James Whitcomb Riley, "The squirt gun uncle maked me". The same thrill was here.

Well, then we took an auger bit and went to the mammoth tree. Daddy drilled two holes about 3 inches apart and 2" deep in the friendly old maple tree, into which he drove the spiles, as they were called, and immediately the wonderful sweet water, called sap, began to flow. We rushed back to house to get some pans and pails. Against the tree, we piled some flat stones, on which we set the pans, and our happiness began. This was the beginning of some very wonderful times making maple syrup and sugar in later years. This particular time, which gave such a thrill, had its difficulties later. We had no way to evaporate the water to get it to that sticky, sweet stage known as maple syrup, except to boil on the kitchen stove. It was supervised by mother, and closely watched by two little rascals. O course not much syrup can be made from 3 or more trees, in this way on the kitchen stove, but mother was very glad to please us. Once in a while she would boil past the syrup stage and put some in a saucer, telling us to stir it until it cools which we did, and pretty soon it turned to sugar. Oh such wonderful stuff. We soon learned to stir it very briskly. The faster we would stir it, the finer and whiter it would get. We did not flood the market with sugar but we had a sweet time. There is almost always "a fly in the ointment" somewhere; I suppose for the purpose of slowing the happiness so that we do not get over enthused, a sort of brake, slowing us down to normal progress. Well, it came one day, when there was a loud snap and sort of sputter, which surprised us very much. The ceiling paper began to unroll, and the first we knew, it was on the floor. It had left the place where we wanted it and lay very contentedly on the floor, where it was not supposed to be. Right there the black eyes of my mother began to exert themselves, as black eyes are sometimes supposed to do, and we knew that, from what she said, our sugar days in the kitchen were memories. We were, of course very sorry and very innocent of the cause, until it was explained that too much steam does not do paper paste very much good. We were not daunted, though, and here is where the phrase of daddy’s took root, "we will find a way". Well, after much thought, my brother and I thought up a scheme, to hang a kettle on a pole and suspend it over a fire. We tried to drive some crotched sticks into the ground, which did not seem to work very well, so we leaned the crotched stick against the apple tree and the other end against the clothes pole. This worked very well, but after the next year, we went to the woods, where we had more trees. As we grew our project grew, as is the way of life. Big things come from little beginnings, sure enough, but not without their usual difficulties or leveling off process. As business grew, we had to resort to better modes of doing it. We could not always depend on the spiles of our first adventure. Better ways must be found. We thought of the idea of using some heavy tin, slightly bent to make trough, which we could drive into the bark of the tree just at the point of a notched v made in the tree. This worked fine and we got along very well until some better Yankee invented a cast iron spile that could be driven into a hole in the tree. A little hook was right on the spile on which a pail could be hung, or a can used in which a hole had been made just below the rim. One of our difficulties was in the fact that if it rained too much, water would get into the sap, which caused either too much boiling, or emptying the pails and starting over. Some other Yankee remedied this by making a cover to snap on the sap can. We were not bright enough for this yet and we were very faithful to the job and did the best we could with what we had and enjoyed every minute of it.

I was always afraid that mother or daddy would not care to have us so far away from the house, using fire in the woods, so I was very careful not to do anything that would cause this to happen, but one day we had some visitors, some neighbor youngsters, and you know that after the newness of anything wears off, something different has to be done. The visitors just could not sit still and watch, so had to get into mischief. When I returned from gathering sap, they had set the leaves afire a short distance away, and I, as well as the rest, was very much scared at what they had done. One little fellow screamed and started for the house. I knew quickly that if he reached the house to tell the news, our little job of making syrup would be all finished. I asked my brother to empty the sap on the fire, while I raced for the boy and overtook him, much to my delight, then I raced back to help put out the fire, all the time wishing that the visitor had not come and would never come again.

When things run along badly and a person gets disheartened, it is so much fun, when the difficulties get smoothened out and back to normal again. "After the brake is released, the wheel turns free."

For a time all was serene, until one day we left for dinner and there were only a few coals, so we did not quench them. When we returned, we found that there was enough heat in the fire that we did not quench, to boil the syrup down until there was only one inch of black substance burned on our three legged kettle. Our syrup was so far beyond the sugar stage that it had reached the charcoal stage, along with my enthusiasm. Father was clearing land down on the flat, and we took our broken hearts to him and cried it out. He was very sympathetic and said "Don’t feel bad, we will find a way to fix it. So he and the hired man, Lewis Petrie went with us, scraped the kettle clean, polished it, and helped us start over again. We thought it pretty nice to have a daddy like that.

Some of the weather in sugaring time is rather bad, and the wind and rain can be very cold and disagreeable. We had no protection from it, so I conceived the idea of fastening some cross poles to four trees that were close to the fire, then we cut some hemlock boughs and laid them on top for a roof, then on the sides we placed short cut pieces of hemlock branches, hooking them over the side poles. It took quite a time to accomplish the task, but finally we finished on open side lean-to, and it caught quite considerable heat from the fire. We were really quite comfortable in the cold weather, and I loved it so much that I dreaded to go home, but our chores had to be done. I still cherish these blessed memories. Life could be very dull without them. I guess it is our duty to do everything today in such a way that it will bring pleasant memories tomorrow. My maple sugar experience in those days put me in good stead for later years, and the thrill of that sweet time still remains.

Our outfit at that time was made up of a three legged kettle about two feet in diameter, hung by the bail over a pole of green timber about four or five inches in diameter, anchored at one end to a tree, on a limb or crotched stick, with the other end leaning against another tree, on a crotched stick. The one end was left free so that, in an emergency, it could be lifted from the crotch and the kettle could be swung quickly off the fire. Maple syrup near the end of the boiling stage sometimes foams and if not watched closely, will go over the top, which made it necessary for quick removal. It can sometimes be controlled by stirring, and sometimes we would suspend a piece of fat pork from the pole to a point one inch below the top of the kettle. Usually, when the foam touched this, it would subside. This latter way seemed most popular with us, for the reason that the pork would get cooked in the steam and acquire a wonderful taste, which caused us to keep asking for more pork, until mother sensed something strange. After a few questions, we admitted that we ate it. Then she laughed hilariously, but we got the pork just the same.

When the maple trees start to bud, the sugar season is at an end, because the sap sours and becomes milky and not very appetizing, so this little wonderful time is done and other activities must occupy our minds. The buckets are gathered and washed, the kettle is thoroughly scrubbed and made ready for other uses, and we bid adieu to a most delightful experience.

The memory of those first maple sugar instances at home remains very pleasant to this day. Even in the years that followed, maple sugar time was one of the best times of the year for me. There were a number of what we called sugar bushes around the country. Why they were called sugar bushes I do not know. They were considered very important because at that time of the year nothing else could be done on the farm, while they gave opportunity of deriving a bit of money at a time when the heavy winter had about dissolved the ready cash.

In a wooded area across the field in front of our old home, was a sugar bush of quite importance, owned by Mr. Henry Petrie, who lived at the foot of the hill where we rode down hill on our sleds. We as well as other boys would congregate evening to watch the boiling process, which was done in a large, long pan, about seven feet long, two and one half feet wide and six inches deep, which rested on a well laid stone fire box. Sometimes there was smaller pan, back of the large one. This was called the syruping off pan. There was a large tank just outside the building that held usually about ten barrels of sap as it was gathered from the tapped trees.

The gathering of the sap was great sport. A large tank or barrel, on a set of bobsleds, drawn by a team of horses, was filled with sap as the team was driven around from tree to tree, then emptied into the larger on at the sugar house. From this larger one, a pipe carried a small stream of sap to the boiling pan in a right amount to keep the pan full as the boiling process evaporated the water. The cloud of steam that escaped through the ventilator on the peak of the roof, made quite a sight to our young minds. When the sap in the large pan became quite syrupy, a quantity was dipped into the smaller pan to be boiled down without further addition. When this was at the right consistency, it was removed from the pan. This was called syruping off. It had now reached the stage of about eleven pounds to the gallon and it could be kept for quite a long time without "sugaring".

Frequently, some was boiled to a heavier consistency and we would get a pan of clean snow and put some syrup on the snow. It would get hard from the sudden chill, forming a delightfully fine wax. We called this waxing. At such times there would be quite an assembly of people, who would sit around the fire, tell stories, sing, and eat wax. Of course, if you have never tried this, you do not know the wonderful times you have missed. On boiling the syrup slightly more, it forms sugar on cooling, and by stirring real fast until it sugars, it forms a very light colored fine grain sugar that is wonderfully appetizing.

Sometimes during the season, the young men that assembled would draw straws to see which one should go "borrow" a hen or two from some of the sleeping farmers, and would cook or roast them at the shanty fire. They say that stolen kisses are the sweetest, and the chickens seemed to taste the sweetest, they said.

I remember one time in particular, when a young man who was living at our house, was elected to get the chickens, and as he remembered that Mrs. Jennings, my mother, had some prize Plymouth Rock chickens of excellent size, he decided to "borrow" a couple from the grape vine trellis on which they roosted at night. It was an extremely dark night. My father had been out to the barn to see if everything was all right before going to bed and was at the corner of the house with the dog at his side, when the dog growled faintly. Daddy hushed the dog and listened until the chickens had been safely removed and the started away with his prize. Daddy said "sick-em" and the dog did. There was quite a commotion of running feet, squawking hens and growling dog. Nothing was said next morning for the chickens were all there much to everyone’s surprise, especially to my father. A long time after that, I suppose the secret could not be kept any longer, the hired man told father how he took the chickens and what a time he had with the dog and chickens. He hit the dog over the head with a chicken that was held by the feet. Then the dog grabbed him by the pant leg and caused his foot to lock behind the other one and him to fall down. This dept up for quite a distance until the dog finally gave up and went home. He took the chickens to the sugar house where the others were waiting, and as he prepared to dress them, or rather undress them for cooking; His conscience began to bother him until he told the boys that he just did not have the heart to destroy Mrs. Jennings’ prize chickens. So he put them back and went nearly a mile to where someone lived whom he did not like very well, then borrowed some more. I guess they tasted all the sweeter.

I was too young to have any part of these parties, but maple sugar time had its thrills for me in other ways that were perfectly legitimate.

One April first, our next door neighbor, Mrs. Petrie sent to my mother some nice looking maple sugar, into which she had mixed liberally some cayenne pepper. Mother did not call the fire department, as she would like to do, because there wasn’t any, but she said "I’ll get even", a common expression then as well as now. I do not know whether she did or not, but when those black eyes of hers snapped, usually something happened. She was a good sport always and could see a joke a mile away. She enjoyed one on herself better than on the other person.

Sugaring time sure had its thrills and pleasures, but it also had its trials and plenty of hard work. Very much time through the winter was spent in cutting wood and hauling it to the sugar house. I took a lot of it to keep a good hot fire for all day and some times all night, for room had to be maintained for the new sap that was accumulating while the sun was shining and if the night remained warm, it would be dripping all night, and morning would find in each sap pail eight quarts of the wonderful sweet water. A well developed tree could have two and sometimes three buckets. Two spiles to the bucket could drop, drop, drop quite a liberal supply of fluid. Every grove had as many trees tapped as could be handled by the operator. There were 100 to 200 usually, which means there would be 300 or 400 eight quart pails of sap, and, as the butches said"That is a lot of baloney!" Maybe you think that I am giving you a lot of baloney, but they are the facts as I saw them, and, because of the fun, the thrill, and the syrup, they remain freshly sweet in my mind fifty years afterward.

Other things remain in my mind that were not so sweet such as a period of very warm weather, when the snow would disappear and we would have travel in the mud and slush; or when a very hard freeze would cause a stoppage of the sap flow. Then the spiles had to be removed and trees re-bored, which was like beginning all over again. Sometimes a rainy spell would cause more rain water to be in the pails than sap. In that case, it usually meant emptying the contents on the ground, rather than consume that much more wood to boil out the excess water. Then at the end of the flow, in the clean up process, the equipment had to be gathered, boiled and scrubbed. It was stored until such a time as the thrill was revived for another syrup spree.

As time progressed, better methods were used, but, due to the rising costs of everything, the more places to work which seemed more to the liking of the young men, this sugar art has about succumbed, and today there are but few places where syrup is made outside of Vermont, where it is still a thriving industry. Vermont maple sugar is known far and wide.

All these memories are highly cherished by me.

In the year of 1922, my last venture in maple syrup took place. Nothing out of the ordinary happened, except that I go the thrill a little earlier that the rest of the neighbors. A nice February spell of warm weather came along and I had the desire to start business, contrary to the customary time of March, and contrary to the advice of neighbors who were considered my superiors. Never the less, my desire was too great, so I got out the equipment and started business, much to my delight. I still distinctly remember the feeling that I had when the sap first began dripping into the buckets. Tears dripped from my eyes. My neighbors did not seem to have this thrill and they did it more as a chore that had to be done. Maybe I was a bit different, but when there is a thrill, there is will and way. Daughter Marjory was a seven year old shadow of her daddy, for almost everywhere I was, she was present. She wished a place all her own to make syrup. So I fixed a place for her, similar to my very first try when I was nine years old. I thought that the desire would soon fade away, but to my surprise, it did not, and I watched with pride and amazement to see her faithfully gathering the sap and attending the fire. The accomplishment that resulted, gave her a thrill that she still remembers. She was faithful to the end of the season.

I had been watching very closely the reports and observing the trend of the weather, so that it appeared to be right in beginning when I did. My observations happened to be correct so that I was about, if not the only one to make a good supply of that precious, sweet maple syrup. Mother Nature has her peculiarities and this time I was working with her. The thoughtful neighbors that tried to advise me put out their buckets just in time to gather them up again. Spring came very quickly that year and I was ready for it.

As I mentioned a while ago, our house was banked with straw in the fall. This procedure was for two reasons; First, it gave its usefulness in protecting the cellar from the wintry winds and cold weather, Secondly, and the main reason was that this covering on the ground killed the grass and sod, making a strip two feet wide around the house, of very nice, fine, mealy, dirt, a very fine place for two little boys to play in the dirt. Of course mother must have been happy if not overjoyed about it.

We had a small cast iron train of cars composed of an engine, some coal cars and caboose. They were dumb things, and just could not propel themselves as the play trains of today, but we imagined very extensively, made roads in this soft dirt on which we would haul the train by a string. Sometimes it does not take much to make little boys happy. I remember that other boys would come to play with us and spend all day in this railroading enterprise. Two of them finally learned telegraphy; one became an operator on the Erie Railroad. Who can say that it did not spring from the thrill of this baby train in the dirt?

Of course we did not play in the dirt all the time. There were other things to enjoy. There were trees to climb, eggs to hunt, playing in the barn, jumping from the big beam into the hay mow, and various other things. But I guess the most fun was after mother got the neighbor kids, my brother and I calmed down, when she read from the magazine "The Youths Companion" to us such stories as: The Towpath, First Lieutenant, and Indian stories or Pittamakin and his white boy friend called "almost brother".

In 1888, my father finished his apprenticeship as a carpenter, in Cazenovia, N.Y., where he learned the trade under M.S. Potter, who was his brother-in-law having married mother’s sister, Delia.

We then moved back to Pennsylvania and lived in a little house in Hammond, about a mile down the railroad from the Fall Brook R.R. depot. We remained here about a year, while father built a new house for Uncle John, mother’s brother. The house was built next to the log cabin home of mother’s childhood.

Uncle John McLean married Ada Stevens, of Hammond. To them were born: Henry, Evelyn, Clara and Ida. The latter were about the age of my brother and me, so we were companions and playmates for that year, enjoying to the full every moment, getting into and out of trouble as much as possible.

Crooked Creek meandered by the town and, as lumbering then was the main occupation, a large dam was made on the creek and sawmill was established. Seeing the loads of logs going by to the mill was quite a sight to us. Loads of bark from the hemlock logs were hauled to the railroad for shipment to the tanneries in various parts of the country. Since the bark was taken from the logs in chunks, 16" by 4’, a little craftsmanship or science was needed to separate it from the log without damage or breakage. It remained in the same shape as when on the log, was very light, so a large amount could be placed on a wagon. The wagon had staves on the side, and the driver seemed to be high up in the air. How the load kept from tipping over on the rough log roads, was amazing to us.

Our house was situated far back in the field from the road and on the bank of a small creek or more like a lagoon, for the water seemed to be still. We used to lie down on the bridge and watch the fish through the cracks in the planking. We did not seem to have much luck fishing as there were not many fish caught on bent pins. How my mother allowed us to play around all those ponds without supervision, is amazement now to me. We seemed to survive anyway.

The next year, we migrated back to the old farm, ten miles away where no more fishing could be enjoyed. Mother would get a spell of homesickness, so father would get someone to do our chores and we would all get into the old platform wagon behind daddy’s buckskin team of lively horses, and a riding we would go, back to Hammond to stay Saturday night and until Sunday afternoon, in the first house of father’s construction. It was a very fine and substantial one. It still stands in fine shape after 70 years, with every chance of holding its own for 100 years, or more.

One time when we went to Uncle John’s, as we drove into the barn to unhitch the horses, my eye, which had a roving disposition, seemed to centre on a fishing pole, lying on some nails in the wall with bait already on the hook, as though it had been only recently cast aside. I gingerly climbed down from the wagon, grabbed the pole, and scampered for the creek which flowed past the other side of the barn. I cast the hook toward the creek, when a 14" rainbow came to meet it and nearly threw me off balance in with the fish. But I saved myself and also the trout, and as it fluttered in the wash tub at the well, it was doing exactly as my heart was doing only it was not in the tub.

Crooked Creek, in those days, was a good size stream, and many are the stories that were told by mother, of her fishing episodes up and down the baby river. In or around the mill dam, many eels were caught, some of large dimensions, and the snakey looking fish made excellent eating. My aunt did not like to cook them because sometimes they would turn over by themselves in the fry pan like they were still alive, but they did not seem to flop around after we had eaten them.

Many, many happy times were spent on week ends at Uncle John’s, when maybe we would all go after wintergreens at the foot of the mountain, or go to the "Cold Spring", or maybe take a walk up Stevenhouse Run, or perhaps try to climb the mountain. Usually it does not take much to interest youngsters.

When the railroad, leading from Antrim to Corning, was being constructed for the purpose of opening the coal fields in the southern part of Tioga County, at and near Antrim, the road went right through the yard of mother’s family at Hammond, separating the old log cabin from the barn. The rails were no more than twenty feet from the barn. Of course, this caused quite a commotion. In later years after the new house was built and old log house torn down, a board fence was built bordering the railroad. As there was no railroad near our home in Charleston, the one at mother’s old home was a great attraction to us kids. Whenever a train would go by, we would rush to the fence and watch in great excitement. Finally, grandpa, scared at our being so close to the train, warned us very emphatically as to what would happen to us if we did not stay away from the fence. He tried to tell us how there might be an accident in which we would be involved.

A water tank for supplying the engine with water was built in one corner of the yard, and about every train would stop here for a supply of water. The coal trains, so heavily loaded would have difficulty in stopping and starting, so the engineer got the idea of detaching the engine about a mile or more up the track and racing ahead to fill up at the tank, by the time the train reached it. Mostly this was accomplished with good results and seemed to work very well. One day we had to hang on the fence to watch the train coming in to be hitched to the engine. A brakeman always rode the front car to operate the brakes if the train were going too fast. At this particular time, as the train had reached the spot where we were assembled, the brakeman seemed to be extra busy. The car on which he was riding began to bump along so roughly that the brakeman was thrown off. The car was off the track and bumping on the ties. There we were where we were told not to be. Maybe the reason that we remembered this so well was because of what happened in the woodshed shortly after. I’m not telling, as the memory is too sad.

This railroad was first called The Antrim, Cowanesque &Corning. Later it was called The Fall Brook. When it was extended to Williamsport, it was called The Fall Brook Division of the New York Central. The first railroad here was completed in 1872. In 1959 it is still in use, though the Antrim coalfields have ceased to produce.

One day, when we were visiting at Uncle John’s, cousin Henry brought out the shot gun that we had been allowed to use during some hunting trips in the nearby woods, always of course when accompanied by Uncle John, to see that we always did what was right with the dangerous fire arm. While examining the gun in the absence of Uncle John, Henry said, "My cousin says to nearly sever the shell between the two wads that separate the shot from the powder, and it will shoot like a bullet, so let’s try it". Of course we did. We did not know what to shoot at until we decided on the outhouse door. The results were amazing. There was already an ornamental opening like a new moon, for ventilation near the ridge of the roof, but we had established a real one in the door, in fact, about half of the door. Then in the absence of Uncle John, we had to try it again. This time we shot at the boxcar that stood on the switch. We were going to make a small ventilating hole in one side of the car, but we did it a little better, as the hole was much too large. When we happened to look at the opposite side of car, we sure had done a good job, as there was an enormous ventilating hole that seemed lots too large. There was quite a commotion in the woodshed when Uncle John came home, so we surely did not try that thing again.

Memories of the trips to Uncle John’s are very much cherished, nevertheless. Ralph and I used to help in the cultivation of tobacco. Gathering hickory nuts and chestnuts in the fall was a great sport, but we had other duties to perform on the old farm back home, and the trips to Uncle John’s became farther and farther apart, as the excitement at home filled our minds.